How are media discourses impacted by the use of different languages?

A comparison of the French, English, and Arabic discourses on France 24 regarding freedom of expression and Islam

Table des matières

Texte intégral

1Résumé

L’objectif de cet article est d’étudier la manière dont les langues médiatiques de France24 contribuent à façonner les débats, notamment celui sur la liberté d’expression et l’islam. L’étude se base sur un corpus sélectionné à partir des chaînes YouTube en français, en anglais et en arabe de France24, corpus qui contient des vidéos publiées entre le 16 octobre et le 16 décembre 2020, c’est-à-dire dans les deux mois suivant le meurtre de Samuel Paty. L’article propose une analyse du discours qui se concentre sur les structures lexicales et syntaxiques. Les collocations et les fréquences sont également prises en compte pour examiner les différences et les similitudes dans l’utilisation des langues française, anglaise et arabe sur France24. Les différences entre les trois langages médiatiques incluent la manière dont la liberté d’expression est désignée, les collocations utilisées et le degré de différenciation lorsque l’on fait référence à « eux » (versus « nous »).

Mots-clés : France24, discours médiatique, langue de diffusion, liberté d’expression, islam

Abstract

This article aims to investigate three media languages on France24 based on discussions regarding freedom of expression and Islam. The corpus was selected from France24 YouTube channels produced between 16.10.2020 to 16.12.2020; in the two months following the murder of Samuel Paty. These discussions are examined using corpus-based discourse analysis focusing on the lexical and syntactical structures. Collocation and frequency analyses are also carried out to examine the differences and similarities in the use of English, Arabic and French languages on France24. The findings reveal that the discourses on France24 are affected by media language. The differences in the three media languages include the way freedom of expression is referred to, the collocations used, and the level of differentiations when referring to “THEM” (versus “US”).

Keywords: France24, media discourse, broadcast language, freedom of expression, Islam

Introduction

2The world witnessed a cultural clash shortly after the republishing of controversial cartoons by the French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo, in September 2020. Tensions were then escalated after the murder of Samuel Paty1 who used these caricatures in the classroom to explain freedom of expression. These caricatures were considered by some as a commitment to freedom of expression and by others as thoughtless provocations of Islam. In several countries, demonstrations took place to oppose this practice of freedom of expression. Different campaigns have also been launched on social media calling for the boycott of French products. These opposing views show that the limits of freedom of expression are still controversial in different cultures and countries. This article examines the English, French and Arabic discourses on France24 regarding freedom of expression and Islam broadcast after Samuel Paty’s death. Comparing these three languages will provide an overview of whether and how discourses on the same media channel are affected by media language.

3Linguistic research into media discourse, or what is called ‘media linguistics’ (Perrin, 2017), is related to several other subfields (sociolinguistics, pragmatics, ethnography, discourse analysis etc.), and examines various phenomena such as language change, variation, style, genre, register etc.; conversation, relevance, politeness etc.; routines, value systems etc.; reported speech, conversation, framing, stance etc. (Cotter & ben-Aaron, 2017, p. 45-46). By ‘media discourse’ we understand the “interactions that take place through a broadcast platform, whether spoken or written, in which the discourse is oriented to a non-present reader, listener or viewer”, following O’Keeffe’s definition (2012, p. 441). The novelty of our study consists in its comparison of the language versions of the transnational news channel France 24, which to our knowledge has not been the subject of any research from the perspective of media linguistics. This article aims to answer the following research questions:

4Q1: What are the differences and similarities in the French, English, and Arabic discourses on France24 when discussing freedom of expression and Islam?

5Q2: How does “THEM” (as opposed to “US”) differ in the French, English, and Arabic discourses on France24 when discussing freedom of expression and Islam?

6In this paper, both qualitative and quantitative methods will be considered. For the qualitative method, interdisciplinary critical discourse analysis will be carried out with a focus on the lexical and syntactical structures. This framework includes examining the different ways freedom of expression and Islam were discussed on France24. It also includes an analysis regarding “THEM” as opposed to “US” and how it is used. Collocation analysis will be carried out on Islam, Islamist, Muslim, freedom, and republic. For the quantitative method, frequency analysis on these five keywords will be conducted. The structure of this article is divided as follows: First, freedom of expression and Islam related concepts will be discussed. Second, the corpus and methods used will be explained. Third, the analyses and results section will include a comparison of the description of freedom of expression in the three languages used on France24; a collocation and frequency analyses of five keywords and the use of references using “THEM”. This article concludes with a discussion of the differences and similarities present in the three languages used on France24.

Freedom of expression and Islam related concepts

Freedom of expression

7The term freedom of expression is far from being recent; it dates to the late 6th or early 5th century BC (Wallace, 2007, p. 65). Although freedom of expression has a long history, it still succeeds in generating controversies over where limits should be set. What happened in France in September 2020 proved that the limit on freedom of expression and the way it should be applied are still unclear (Ellian & Molier, 2015, p. 3). This ambiguity raises the question of whether the definition of freedom of expression is the same in different parts of the world.

8In this paper, the meaning of freedom of expression embraces the principle that individuals have the right to express their opinions and ideas through speech, texts or in art forms without resulting in any form of punishment or censorship. This definition is based on the one established in Article 19 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Both these articles underlie the importance of holding opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation. In most of the Western world, freedom of expression is considered to be one of the key tenets of human rights and democracy which has been emphasized since the Enlightenment.

9Freedom of expression is restricted in most Muslim majority countries particularly as regards criticizing an object of religious or political reverence. Insulting Mohammed is considered an even more serious offence than insulting God (Langer, 2014, p. 332). In Islam, the true meaning of freedom is found in the relationship of man to the divine (Rosenthal, 2015, p. 110). Thus, freedom, in a way, involves being subservient to God. Indeed, blasphemy laws remain an issue in many Muslim majority countries (McAuliffe, 2020), and in a number of countries where Islam is the state religion or where Muslims are in the majority, laws criminalizing blasphemy often entail punishments. Hence, freedom of expression can be seen to exclude critical discussions about religions (Langer, 2014, p. 331). The meaning of freedom of expression in Muslim majority countries clearly deviates from the one practiced in the West. While Western liberal ideas evolved as a key tenet for human rights, the idea of freedom did not evolve in many Muslim majority countries in the same direction.

10Freedom of expression can have different meanings in different parts of the world. As it is a cultural practice, individuals learn its meaning from experience and the practices of everyday social life (O’Donovan et al., 2018, p. 18). Therefore, critical judgement regarding freedom of expression could be limited as is the case in many countries that still adopt blasphemy laws. It is crucial to be aware of these differences when comparing how different media languages report on freedom of expression.

Islam related concepts in media discourse

11In this section, semantic nuances of certain concepts: Islam, Islamist (Islamism), radical Islam and terrorism will be discussed. Islam is the monotheist religion of Muslims; its origin is placed around 610 CE (Gregorian, 2003, p. 6). This definition of Islam is the simplest to grasp. The confusion begins with the idea that Islam is synonymous with Islamism. The former is described as a religion, while the latter claims to be a political system (Olsson, 2021, p. 4; Tibi, 2012, p. 2). Islamism is described as the act of advocating the establishment of an "Islamic order". It is important to note, however, that it does not specify the use of force or violence (Krämer, 2003, p. 536). Thus, this term is not a pejorative per se, yet it has been used negatively in many instances in media discourse.

12Research has also shown that the issue of the extent to which Islamism is inextricably linked to terrorism is still unresolved as most Islamist activists reject the use of violence (Hoewe & Bowe, 2021, p. 1015). Lewis (1988, p. 72) argues that describing extremist actions using the terminology Islamist is “counter-productive and damaging to community relations”. It serves the purpose of terrorism but also increases the division between communities which leads to Islamophobia (Abbas, 2012).

13In addition, in the context of terrorism coverage, the degree of differentiation between Muslims and terrorists matters greatly (Matthes et al., 2020, p. 2147). Differentiation between Muslims and terrorists is crucial as it can fundamentally affect the way citizens judge out-group members of different origins and religions. Interestingly, it has been shown that Muslims sources usually differentiate between Muslims and terrorists in the news. In non-Muslim sources, however, they are less likely to engage in this differentiation (Matthes et al., 2020, p. 2147).

14When it comes to “Radical Islam”, it is worth noting that the adjective radical is a relational concept referring to something that is not regarded as a norm (Olsson, 2021, p. 7). The relationality manifests in the fact that certain forms of thoughts and behaviors could be regarded as radical by some but as normal by others. “Radical Islam” can be interpreted in several ways depending on one’s political orientation (Hoewe & Bowe, 2021, p. 1015). The expression “Radical Islam” is not negative per se. nevertheless, according to Olsson (2021, p. 1) “Radical Islam” is often equated with terrorism leading a Muslim to be suspected of being at least a potential terrorist. In this regard, Hoewe and Bowe (2021, p.1015) argue that news content that attributes an attack to “radical Islam” rather than “terrorism” can result in increased islamophobia. Thus, attaching the adjective 'radical' to Islam makes it difficult for many non-Muslims to distinguish between the noun and the adjective. In 2016, Obama was reluctant to use collocations such as “Radical Islam” and “Islamic extremism” when describing an attack in connection with the Orlando nightclub massacre2. The use of such terms could result in misrepresenting all Muslims as potential terrorists which shows the importance of upholding a critical and analytical perspective (Olsson, 2021, p. 1). In this context, it is crucial to be aware that many radical Muslims are not terrorists (Hoewe & Bowe, 2021, p. 1015). Keeping such nuances in mind, i.e. Islam, Islamism, and radical Islam is a fundamental requirement in the analysis of the three languages on France24.

Materials and methods

Materials

15This article is an attempt to examine the interrelation present between media language and the concepts discussed on France24 through a corpus-based media discourse analysis. France24 (hereafter Fr24) is a French state-owned international news television network based in Paris. Its channels broadcast in French, English, Arabic, and Spanish and are aimed at overseas markets. The corpus is selected from Fr24 French, English and Arabic YouTube channels. It is composed of 72 videos found on Fr24 YouTube channels, divided as follows: 24 used for the English corpus, 18 for the Arabic corpus and 30 for the French corpus. In the analysis, these will be referred to using ‘language + number’.

16The videos were collected carefully according to their date of publication and most importantly their titles. The selected period for the corpus was from 16.10.2020 to 16.12.2020; two months following the killing of Samuel Paty. The titles of the videos selected were those that included any of the following keywords: Islam, freedom of speech, freedom of expression, Samuel Paty, boycotting. The search for the videos was very feasible as the Fr24 YouTube channel provides a search box where it is possible to type in a keyword and select a date. By doing so, all the relevant videos for the date and topic appear in a list. All the relevant videos were therefore downloaded using YouTube video downloader. The final stage of data collection consisted of transcribing the videos into texts. For this step, it was important to consider software that transcribed in English, French and Arabic. In this research, Sonix AI and Otter AI, online audio and video transcriptions programs were used. Following the transcriptions, the number of words for each corpus was: 48,295 for English, 60,484 for French, and 23,342 for Arabic.

17Corpus tool AntConc (Anthony, 2021) version 4.0.2 was selected for the analysis of the data. The reason for the choice of this version of AntConc was based on its ability to transcribe in English, French and Arabic; the three languages that were crucial to conducting this study. In this study mainly word frequencies, collocation and concordance were used. Collocation refers to a natural combination of words that are closely affiliated with each other. It provides an overview of the recurrent patterns in the discourse which facilitates textual analysis. KWIC concordance is a list of target words extracted from the corpus that indicate the context in which the word is used. In our analysis, the examples were translated with the help of Google automatic translation and revised by the authors to ensure their accuracy.

Methods

18This study belongs to media discourse analysis, which is placed under the broad umbrella of discourse analysis (Cotter & ben-Aaron, 2017, p. 49) and has two key components at a linguistic level: (1) media texts and images, and (2) the social practices and processes behind producing and receiving media texts and images (Pleshakova, 2017, p. 77). However, in this research, only the textual component was taken into consideration, excluding image and multimodality. Therefore, the media discourses under analysis included only the spoken dimension of news items broadcast on the three Fr24 YouTube channels, which were later transcribed into texts.

19In this article, discourse analysis was conducted at the lexical and syntactical levels in order to examine and compare the description of freedom of expression in the Arabic, English and French discourses on Fr24. This approach is inspired by the work of Van Dijk (2006) that investigated the link between discourse and ideology. In this study, referring to ideology would be too broad as our focus was limited to discourse about freedom of expression. However, we have critically analyzed the discourses with a focus on the lexicon and syntactical structures according to Van Dijk’s method (2006, p. 125).

20Following critical discourse analysis, collocation and frequency analyses will be carried out as they have the potential to provide insights into lexical connections in discourse (Brezina et al., 2015, p. 142). The number of occurrences of freedom of expression will be normalized. The formula used to normalize the frequencies follows the example provided by Ippolit (2013, p. 34) which is the following: Frequency per million words (pmw) = number of instances/ number of words X 1,000,000. With (/) standing for the division sign, (X) standing for the multiplication sign and (=) standing for equal sign. In addition, the results were rounded up for the sake of clarity. AntConc enabled the identification of keywords frequencies, collocations, and concordances. In this article, collocation is defined as the co-occurrence of words as observable in a corpus (Gerbig & Mason, 2008, p. 200). There are three criteria for identifying collocations: (i) distance, (ii) frequency, and (iii) exclusivity (Brezina et al., 2015, p. 140). The distance specifies the span around the keyword which can be as little as one word. The second criterion, frequency of use, is an important indicator of the typicality of word associations (ibid). In this study, a span of five words to the left and five words to the right were investigated. For the frequency, the three most frequent collocations were selected. The exclusivity was not considered in this research. The collocations selected did not include prepositions (of, in, at…) as these functional words are insignificant in relation to this study.

21The study also accounted for the ways “US” and “THEM” were referred to in Arabic, French and English discourses on Fr24. This analysis is inspired by the Ideological Square Model that was presented by Van Dijk which specifically focuses on the polarizing macro strategy of ‘positive self-representation and negative other-representation’ (Van Dijk, 2006). This analysis was possible by examining the context in which freedom of expression occurred using the AntConc’s concordance tool. The use of “THEM” was detected by observing the ways in which the OTHER (the person or object that represent the threat) was referred to in the discourse, while the use of ‘US’ was discovered by observing the supporters of freedom of expression.

22The comparison of the way freedom of expression is reported in the Arabic, English and French discourses on Fr24 was possible through qualitative and quantitative analyses including collocation and frequency analyses in each language.

Analysis and results

Freedom of expression

23Freedom of expression is considered an important and positive value in English, French and Arabic languages on Fr24. In English, it is depicted as “very precious”; in French as “treasure” (trésor) and “dear to European values” (chère aux valeurs européennes); in Arabic as “حق لا يقدر بثمن” (priceless right), “القداسة” (sacred) and “من القيم الإسلامية” (among Islamic values).

24Only in the French and English discourses, is freedom of expression described as threatening. This description is illustrated through the use of lexicon such as “endangered”, “menaces” (threats), “attaquée” (attack) and “bataille” (battle) as seen in examples 1 — 4. This state of threat seems to be absent in the Arabic corpus.

1.Very precious and always possibly endangered (English-11)3

2.Des représentants de médias français se sont réunis pour débattre des menaces qui pèsent sur la liberté d’expression (French-6) - (French media representatives gathered to discuss threats against freedom of expression)

3.Vous êtes optimiste quant à la liberté d’expression en France dans les prochaines années? Vous estimez qu’elle est attaquée, peut-être de toutes parts. Est-ce que cette liberté d’expression, elle vivra toujours en France ? (French-4) - (Are you optimistic about freedom of expression in France in the upcoming years? Do you feel that it is under attack, perhaps from everywhere? Will this freedom of expression always live in France?)

4.Et que la liberté d’expression doit être une valeur, au moins en Europe, France et en Europe, est une valeur fondamentale qui doit être vraiment gravée dans notre cœur parce que c’est toute nos valeurs qui se joue aujourd’hui dans cette bataille (French-20) - (And that freedom of expression must be a value, at least in Europe, France and in Europe, is a fundamental value that must be truly engraved in our hearts because it is all our values that are being played out today in this battle)

25In the English and French discourses, there is an impression that protection, resilience, and continuity of freedom of expression are the solution to outliving this threat. This is constructed lexically through “defendre” (defend), “réarmer la culture” (to rearm the culture), “never give in”, as seen in the examples 5 — 7.

5. Nous ne nous laisserons pas intimider et nous continuerons à défendre notre mode de vie Européen (French-10) - (We will not be intimidated, and we will continue to defend our European way of life)

6.réarmer la culture qui est une culture laïque de défense de la liberté. (French-29) - (to rearm the culture of secularism, defense and freedom)

7.France will never give in on freedom of expression (English-4)

26Example 6 includes a figure of speech “to rearm the culture of secularism”, a metaphor that emphasizes the secular and liberal culture that needs to be reinforced in France.

27Freedom of expression is presented as having the ability to provoke Muslims and to anger the Muslim world in the English, Arabic, and French corpora:

8.French politicians and many citizens have since widely displayed the images in the name of freedom of expression, prompting an outpouring of anger in parts of the Muslim world (English-15)

حرية التعبير يبدو أنها تستفز خارج حدود فرنسا، فتخرج الأفواج غاضبة من الكويت إلى بنغلادش منددة بفرنسا9.. (Arabic-9) - (The Muslim in France feel provoked because of the free speech that is present in the country)

المسلم في فرنسا يشعر باستفزاز بسبب حرية التعبير الموجودة في هذا البلد10. (Arabic-9) - (The Muslim in France feel provoked because of the free speech that is present in the country)

11.[…] entre la liberté d'expression et la volonté délibérée d'offenser les sentiments des musulmans, le devoir de la fraternité nous impose à tous de renoncer à certains droits pour que la fraternité règne dans notre pays (French-18) - ([…] between freedom of expression and the deliberate desire to offend the feelings of Muslims, the duty of fraternity requires us all to renounce certain rights so that fraternity reigns in our country)

28Examples 8—11 demonstrate that in the three media languages on Fr24 there are references to the fact that freedom of expression does provoke Muslims both inside and outside of France.

29The extracts explaining the functions of freedom of expression seems to be much more recurrent in the Arabic corpus compared to the French and English. For example, freedom of expression is depicted as a (1) heritage of the French Revolution; (2) among French values; and (3) a way to protect any attempt to control the masses as seen in the examples below:

حرية التعبير إرث من الثورة الفرنسية، وهي من الحريات الأساسية المترسخة في إعلان حقوق الإنسان والمواطن12.(Arabic-9) - (Freedom of expression is a heritage of the French Revolution, one of the fundamental freedoms entrenched in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

في فرنسا في جمهورية لها قيم من أهم قيمها قيم الحرية والعدالة والمساواة، المساواة، حرية التعبير13. (Arabic-13) - (In France, in the republic holds values of freedom, justice and equality, equality, freedom of expression)

حرية التفكير و حرية التعبير وحرية سخرية تحمي المكونات كلها داخل الدولة من أن يطغى أحدهما على الآخر. نحن حينما14 نستخدم الصحافة نسخر من الناس نسخر من الأفكار. نحن بهذه الطريقة نضع حد لكل محاولات السيطرة على على الجماهير. (Arabic-9) - (Freedom of thought, freedom of expression and freedom of sarcasm protect all components within the state to rule over each other. When we use journalism, we make fun of people and make fun of ideas. In this way, we put an end to all attempts to control the masses)

Another interesting observation concerns the extracts clarifying that freedom of expression is among Islamic values are only present in the Arabic language as seen in this example:

من القيم الإسلامية. حرية التعبير هي من المقدسات التي جاء بها رسول الله سلم يضمن للناس جميعا حرية التعبير وحرية الرأي15 وحرية الاعتقاد (Arabic-8) - (Among the Islamic values, freedom of expression is one of the sacred things that the Prophet introduced that provide to all freedom of speech, opinion and thought)

30In addition, only in the Arabic corpus, are there references clarifying that the French president Macron is defending freedom of expression and not the caricatures of Charlie Hebdo picturing the prophet.

الاستفزاز الذي جاء هو من لسان الرئيس الذي اشتبه قوله انه يدافع عن شارلي إيبدو، وهذا غير صحيح، إنما الرئيس الجمهوري16 الفرنسي لم يدافع إلا عن حرية التعبير، (Arabic-9) - (The provocation that came from the president who was suspected of defending Charlie Hebdo, which is not true, but the French Republican President only defended freedom of expression)

31Table 1 summarizes these observations, and also quantifies them. The numbers present in this table were normalized to 1,000,000 words in order to compare them objectively.

Table 1. Freedom of expression occurrences

|

Freedom of speech/expression: |

English corpus |

French corpus |

Arabic corpus |

|

Is a positive value |

83 |

149 |

214 |

|

Is threatened |

145 |

165 |

0 |

|

Needs protection |

83 |

16 |

0 |

|

Provokes/angers (sometimes to the Muslims/Muslim world) |

41 |

16 |

128 |

|

Explanations: origin and functions |

124 |

33 |

214 |

|

Questioning free speech and its limits and cause debate |

83 |

132 |

214 |

|

As a subject in school |

41 |

50 |

128 |

|

Problem to teach it |

0 |

83 |

43 |

|

Caused the killing of Samuel Paty |

0 |

66 |

0 |

|

Clarifying president Macron defends freedom of expression and not the caricatures |

0 |

0 |

343 |

|

Clarification: is among Islamic values |

0 |

0 |

128 |

|

Number of occurences |

600 |

711 |

1414 |

32Table 1 presents three insightful observations. First, freedom of expression is only considered threatened and in need of protection in the English and French corpora. Second, clarifying that president Macron is defending freedom of expression and not the caricatures targeting Islam is only present in the Arabic corpus as seen in example 16. This clarification is also the most frequent description of freedom of expression in the Arabic corpus. Thirdly, the representation of freedom of expression as being an Islamic value is only present in the Arabic corpus.

Frequencies and collocations

33Frequency and collocation analyses were performed on the following keywords: freedom, Islamist, Muslims, Islam, and republic to have an overview on the occurrence of these concepts in the three corpora from Fr24. These keywords were selected based on the ways freedom of expression was described in the corpus.

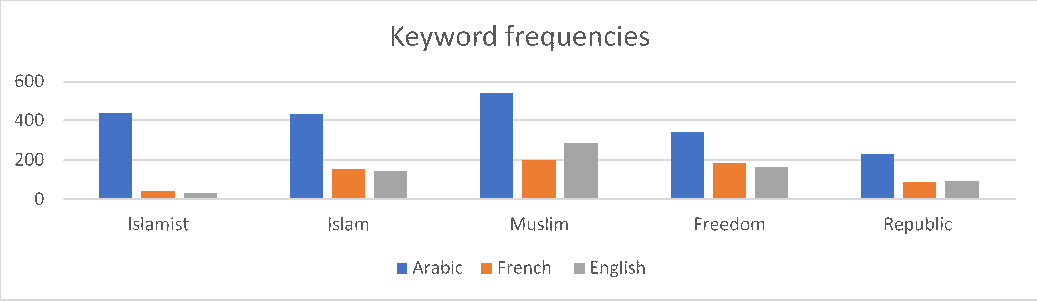

Figure : Keyword frequencies in Fr24 English, French and Arabic

34Based on Figure 1, Islam, Islamist, Muslim, freedom, and republic occur significantly more frequently in the Arabic corpus compared to the English and French corpora. For the English and French corpora, the difference is not significant.

35Examining the three most frequent collocations of these concepts reveals some differences in the English and French corpora compared to the Arabic corpus. Table 2 shows that in the English and French corpora, Islamist collocates with negative concepts linked to terrorism, extremism, radicalization, and suspicion. In the Arabic corpus, however, Islamist collocates with more neutral concepts which are: world (العالم), religion (الدين), and countries (الدول). Even though, the term Islamist is significantly more frequent in the Arabic corpus, the three major collocations are not pejorative in Arabic.

36One similarity among the three corpora is the collocation of Islam with the term political. Based on Table 2, there are significant differences between the French and English corpora compared to the Arabic corpus. The most frequent collocations of Islam were overall negative in the English and French corpora where it collocates with radical, against and political. This confirms the previous research that found that the term radical collocates with Islam in many instances in the Western media (Abbas, 2012; Olsson, 2021: 1). For the Arabic corpus, however, the three most frequent colocations of Islam were neutral. Unlike, Islam and Islamists, the term Muslim collocates with concepts “countries”, “world”, “French”, “religion” in English, French and Arabic discourses of Fr24.

Table 2. Islamist, Islam, and Muslim collocations

|

Concepts |

English |

French |

Arabic |

|

Islamist |

Terrorism Suspect Extremists |

Terrorist (terroriste) Radicalize (radicalisent) Terrorists (terroristes) |

العالم (World) الدين (Religion) الدول (Countries) |

|

Islam |

Radical against Political |

Contre (against) Politique (political) Radical |

political world religion |

|

Muslim |

French France World |

World (monde) Religion (religion) Country (pays) |

France (فرنسا) Islam (الإسلام) Speech (خطابا) |

37Table 3 demonstrates that republic and freedom have neutral to positive collocations in the three languages used on Fr24.

Table 3. Republic, freedom collocations

|

Concepts |

English |

French |

Arabic |

|

Republic |

Values Citizens Hero |

President Values Adhesion |

French Values President |

|

Freedom |

Expression Speech Thought |

Expression (expression) Blapheme (blasphémer) Teach (enseigner) |

Expression Secularism التفكير (Thinking) |

38The three most frequent collocations of republic are relatively positive in Arabic, English and French discourses. Freedom collocates with expression in three corpora. It collocates with speech and thought in the English corpus; with blaspheme and teach in the French corpus, with secularism and thinking in the Arabic corpus. In all three corpora, freedom is linked to being free to express, to think, to blaspheme. It is linked to freedom being taught and to secularism.

39The frequency and collocation analyses provide the following results (1) all the words Islam, Islamist, Muslim, freedom, and republic occur significantly more frequently in the Arabic corpus compared to the English and French corpora; (2) freedom, republic and Muslim have relatively neutral to positive collocations in the three corpora; (3) Islam and Islamist have negative collocations in English and French corpora and neutral ones in the Arabic corpus.

40The collocation analysis presents two insightful observations. First, the term Islamist collocates with terrorists in the English and French discourses on Fr24. Second, the term Islam collocates with radical in the English and French discourse. This leads to many instances of “Islamist terrorist” and “Radical Islam” in the English and French discourses. However, both Islamist and Islam collocate with neutral concepts in the Arabic language such as world, countries, political, and religion.

Concepts and collocations linked to “THEM”

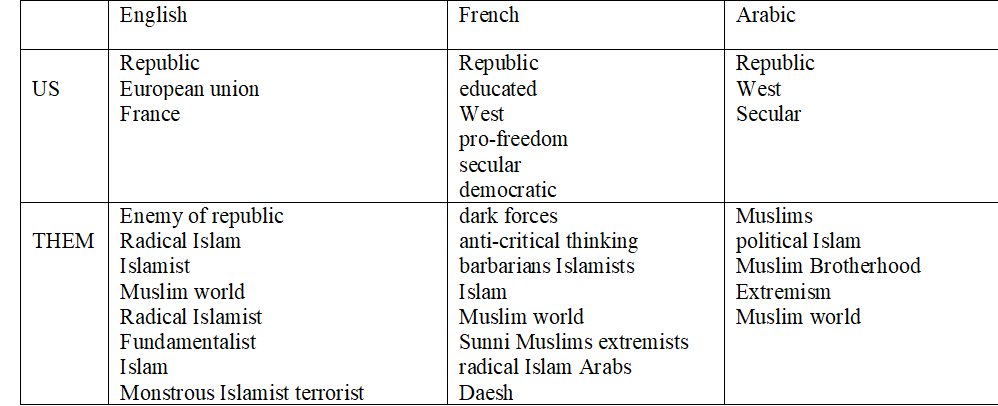

41There are many similarities in the ways “US” and “THEM” were described in the three languages. Arabic and French examples found in the tables below were translated to English. Overall, there is a tendency to refer to “US” as: the republic, West, educated; and “THEM”: the Muslim world, radical Islamist, extremists. The focus in this section is placed on the concepts linked to “THEM”.

Table 4. US VS THEM in English, Arabic, and French

42Examples 17—20 better illustrate the concepts linked to “THEM” in the English and later French discourses. Example 17 indicates that the threat comes from radical Islamist fundamentalists:

17.The threat of radical Islamist fundamentalists in France (English-18)

43Example 17 demonstrates that the OTHER is linked to Islamist terrorist. Another observation concerning example 18 is that it comprises an interesting contradiction. In the beginning of the extract the attack is described as a monstrous Islamist terrorism attack. In a later stage, it is mentioned that French “opened an investigation into the killing for murder with a suspected terrorist motive”. To first describe the attack as monstrous Islamist terrorism, then mention that the attack is suspected to have a terrorist motive brings into question the level of certainty in describing the OTHER.

18.Our unity and strength are the only responses in the face of this monstrous Islamist terrorism. The French anti-terrorism prosecutor has opened an investigation into the killing for murder with a suspected terrorist motive (English-17)

44As seen in example 19 radical Islam is linked to “THEM”. Example 20 indicates that Macron, the French president, links the term Islamists to “THEM”:

19.Turkey has led the charge against France as the Muslim world condemned the publication of such caricatures considered as blasphemous in Islam, he publicly questions Emmanuel Macron has mental health after the French president vowed a tougher stance on radical Islam in response to the killing and said that France will not give up its cartoons. (English-24)

20.On Friday, Samuel Paty became the face of the Republic, of our determination to disrupt terrorists, to curtail Islamists, to live as a community of free citizens in our country; he became the face of our determination to understand, to learn, to continue to teach, to be free, because we will continue to do so, sir (English-23)

45The way Fr24 links Islam, radical Islam, Islamist, and terrorist references to “THEM” brings the use of these terminologies and the degree of differentiation into question.

46In the French corpus, both expressions l’Islamisme radical (radical Islamism) and l’Islam radical (radical Islam) were used to refer to “THEM” as seen in example 21:

21.« le terrorisme a frappé notre pays avec une sauvagerie inouïe. Oui, l’ennemi est là, il est clairement identifié et je n’ai pas peur de le désigner pour ce qu’il est. Car toute ambiguïté à son égard est déjà un début de renoncement. Cet ennemi, c’est l’islamisme radical. C’est une menace permanente. L’islam radical s’est infiltré au cœur même de notre société de tolérance et de liberté. Il se cache, agit dans l’ombre et avec lâcheté » (French-24) - (terrorism has struck our country with unprecedented savagery. Yes, the enemy is here, he is clearly identified and I am not afraid to designate him for what he is. For any ambiguity about him is already a beginning of giving up. This enemy is radical Islamism. It is an ongoing threat. Radical Islam has infiltrated the very heart of our society of tolerance and freedom. He hides, takes action in the shadows and with cowardice)

47Example 21 also contains a metaphor to create imagery for the reader which is translated as follows: Radical Islam has infiltrated the very heart of our society of tolerance and freedom.

48In contrast with the English and French discourses, in the Arabic corpus, “extremist groups” and “radical extremists” were used to refer to “THEM” as seen in examples 22 and 23 respectively:

المجموعات متطرفة تتبنى كل الأفكار الشيطانية ، وليس في الإسلام فقط في كل الديانات22 (Arabic-9) - (Extremist groups adopt all satanic ideas, not only in Islam in all religions)

القتل مورس من طرف شخص ربما يمثل أقلية متطرفة متشددة، والإرهاب يحصد آلاف الأرواح على امتداد العالم 23(Arabic-9) - (Murder sought by someone who may represent a radical extremist minority, and terrorism claims thousands of lives worldwide)

49Investigating English, Arabic and French discourses on Fr24 reveals differences in the ways “THEM” were referred to. In English the concept of “THEM” is linked to Islamist terrorist, radical Islam and Islamists. In the French corpus, “THEM” is linked to radical Islamism and radical Islam. In contrast to the English and French discourses, in the Arabic corpus, “THEM” is linked to extremist groups and radical extremists. These results are aligned with the collocation results that proved Islam collocates with radical in the English and French discourses.

50One insightful observation concerns the differentiation degree between the Arabic corpus compared to the English and French corpora. The tendency to differentiate between Islam, Islamist and extremism is higher in the Arabic corpus compared to the French and English corpora as seen in Table 4.

Table 5. Differentiation of “THEM”

|

English |

French |

Arabic |

|

|

Differentiation |

Regular Muslims versus extremists |

Middle Age Islam versus progressive Islam |

Islam versus Extremism Islam versus Islamists Islam versus Islamic radicalism Muslim world versus Terrorist |

51The only differentiation present in the French corpus when discussing freedom of expression is between Middle Age Islam and progressive Islam as seen in the example below:

24.L’Islam reste figée à une pensée qui a été produite au Moyen Âge. C’est d’abord de soutenir et d’encourager les initiatives comme les nôtres. Elles existent d’un islam libéral, d’un islam progressiste, réformiste, et il y a plusieurs voix d’intellectuels éclairés qui s’expriment aujourd’hui en France. (French-25) - (Islam remains frozen to a thought that was produced in the Middle Ages. It is first and foremost to support and encourage initiatives like ours. They exist of a liberal Islam, a progressive, reformist Islam, and there are several voices of enlightened intellectuals who speak today in France)

52In the English corpus, one differentiation between Muslims and extremists was observed. Even though example 25 includes this differentiation, it does link both concepts to a state of fear:

25.“you know, one of the experts we spoke to advance 24 earlier told us it’s not just Muslim extremists, that are angered by depictions of the Prophet Muhammad, but regular Muslims, how frightened should everyone be?” (English-3).

53Compared to the English and French corpora, the Arabic corpus comprises more instances of differentiation. Example 26 illustrates the differentiation between Islam and extremism:

هذا الهجوم أعاد تأجيج الجدل في فرنسا حول نجاعة كل سياسات محاربة التطرف أمام هذه العملية الوحشية الذي قام بها هذا هذا26. الشاب …وخاصة أن بهذا العمل هو الذي قام بـ كاريكاتورية الإسلام والمسلمين أكثر من الرسوم التي كان يدينها. نعم نعم هو الذي أساء إلى رسول الله، هو الذي أساء إلى الإسلام، وهو الذي أساء إلى صورة الإسلام والمسلمين حبيبنا (Arabic-8) - (This attack rekindled the debate in France about the efficacy of all anti-extremism policies in the face of this brutal operation by this young man who … especially since it was this act that caricatured Islam and Muslims more than the cartoons he condemned. Yes, yes, he is the one who offended the Messenger of God, who offended Islam, and he who offended the image of Islam and Muslims, our beloved)

54This extract explains that in the Arabic corpus, the killer is depicted as unrepresentative of Islam; instead, the attacker is considered the one who offended Islam and Muslims. In this context, the differentiation between Islam and this brutal incidence is also demonstrated. In the Arabic corpus, there is a tendency to show that “THEM” represents extremists and this attack is not a peculiarity of Islam. For instance, Example 27 stresses that terrorist acts are present in all religions:

المجموعات متطرفة تتبنى كل الأفكار الشيطانية ، وليس في الإسلام فقط في كل الديانات، لكن عموم المسلمين لهم يعني اعتبار27. خاص لنا بهم، ومن حقهم أن يستشعروا أنهم وقع استفزازهم أو جرحت مشاعرهم. المهم أن يكون ذلك دافعا لحوار بينهم وبين من يتبنى حرية التعبير التي تجرح مشاعرهم. (Arabic-9) - (Extremist groups adopt all satanic ideas, not only in Islam in all religions, but the general Muslims have their own consideration, and they have the right to feel that they have been provoked or their feelings have been hurt. What is important is that this is a motive for dialogue between them and those who embrace freedom of expression that hurt their feelings)

55Example 28 includes a criticism against some journalists and politicians that blame Islam instead of Islamists, extremists or Islamic radicalism. Thus, a differentiation between Muslims, on the one hand, and Islamists, extremists, and Islamic radicalism, on the other hand, can be detected.

يعني أنت برأيك اليوم المسلم في فرنسا يشعر باستفزاز بسبب حرية التعبير الموجودة في هذا البلد لأن وسائل الإعلام. لا تقدموا28. للحديث عن هذا الموضوع أو تحليل هذا الشيء إلا من طرف أشخاص محللين أو صحفيين أو رجال سياسة ينتقدون الإسلام مباشرة وليس الإسلاميين أو المتطرفين أو الراديكالية الإسلامية، وإن كان هناك بعض المسؤولين يميزون بين ، ولكن أحيانا بما أنه يلتبس الأمور فيما بينهم فيما بينها، فإن الكثير من المسلمين يعني يحسون باحتقار والاستفزاز طبعا المباشر والغير المباشر (Arabic-9) - (I mean, in your opinion, today Muslims in France feel provoked by the freedom of expression that exists in this country because of the media. These subjects are discussed only by experts, journalists or politicians who directly criticize Islam and not Islamists or extremists or Islamic radicalism. Some responsible peope might differentiate between these (terms). As it is a confusing, many Muslims feel looked down on and provoked, of course directly and indirectly)

56In the Arabic corpus, there is another differentiation between terrorists and the Muslim world as seen in example 29. In addition to these differentiations, explaining that these acts are not a peculiarity of Muslims is highlighted in the Arabic corpus.

القتل مورس من طرف شخص ربما يمثل أقلية متطرفة متشددة، والإرهاب يحصد آلاف الأرواح على امتداد العالم، بما في ذلك29 العالم الإسلامي. هناك جدل قائم حول الأشكال التي تجسد بها حرية التعبير (Arabic-9) - (Murder sought by someone who may represent a radical extremist minority, and terrorism claims thousands of lives worldwide, including in that Muslim world. There is controversy over the ways freedom of expression is expressed)

57The differentiation in this extract addresses terrorism as a worldwide phenomenon and not as a particularity of the Muslim world.

Conclusion

58The aim of this article was to examine the way freedom of expression and Islam were discussed after Samuel Paty’s death in three of the different languages used on Fr24. Comparing the three media languages revealed that the discourses are affected by the broadcast language. Freedom of expression includes differences and similarities when discussed in discourses in English, French and Arabic. The similarities include considering freedom of expression as a positive value in all three languages. However, only in the French and English corpora, does it seem to be referred to as being threatened and in need of protection. In the Arabic corpus, freedom of expression occurs the most in a context that clarifies that Macron is not defending the caricatures that target Islam but rather supporting freedom of expression.

59Regarding the collocations of the five selected keywords, the findings reveal that Islamist collocates with terrorist in English and French discourses on Fr24. Islam collocates with radical in English and French discourse. This leads to many instances of “Islamist terrorist” and “Radical Islam” in the English and French discourses on Fr24. Interestingly, both Islamist and Islam collocate with neutral terms in the Arabic language which are world, countries, political, and religion. It is impossible to know how deliberate the use of these linguistic differences is, but there is every reason to question their use.

60The critical discourse analysis conducted on the English, French and Arabic discourses on Fr24, shows that different concepts are linked to “THEM”, such as Islam, radical Islam, Islamist, terrorist, monstrous Islamist terrorist, radical Islamist fundamentalists, Muslim communities, extremist, regular Muslim, and many more. It seems that there are some differences in the English and French languages compared to the Arabic. On the one hand, in the Arabic corpus, the concept “THEM” is generally linked to extremist groups and radical extremists. On the other hand, in English “THEM” is linked to Islamist terrorist, radical Islam and Islamists; and in the French corpus, “THEM” is linked to radical Islamism and radical Islam.

61It has been shown that Muslims sources usually differentiate between Muslims and terrorists more often than is differentiated in non-Muslim sources (Matthes et al., 2020, p. 2147). The findings in this study show that the tendency to differentiate between Islam, Islamist and extremism is higher in the Arabic corpus compared to the French and English corpora. Thus, the degree of differentiation differs not only from one news channel to another but within different languages of the same news channel. In addition, in the Arabic corpus, there is a tendency to explain that these attacks are not a peculiarity of Islam and that they are present in all religions.

62This research could be expanded to cover other semiotic resources such as images shared during the discussion on freedom of expression as many ideas can also be communicated non linguistically.

References

Abbas, T. (2012). The Symbiotic Relationship between Islamophobia and Radicalization. Critical Studies on Terrorism 5(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2012.723448

Anthony, L. (2021). AntConc (Version 4.0.2) [Computer Software]. Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. Available from https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software

Brezina, V., McEnery, T., & Wattam, S. (2015). Collocations in Context: A New Perspective on Collocation Networks. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 20(2), 139–173. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.20.2.01bre

Cotter, C., & ben-Aaron, D. (2017). Discourse approaches: Language in use and the multidisciplinary advantage. In: Cotter, C., Perrin, D. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Media. (pp. 44–61). Taylor and Francis, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315673134

Ellian, A., & Molier, G. (2015). Freedom of Speech under Attack. Eleven International Publishing, Hague.

Gerbig, A., & Mason, O. (2008). Language, people, numbers corpus linguistics and society. Brill, Leiden.

Gregorian, V. (2003). Islam a mosaic, not a monolith. Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC.

Hoewe, J., & Bowe, B.J. (2021). Magic words or talking point? The framing of ‘radical Islam’ in news coverage and its effects. Journalism 22(4), 1012–1030. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918805577

Ippolit, M. (2013). Simplification, Explicitation and Normalization: Corpus-Based Research into English to Italian Translations of Children’s Classics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, UK.

Krämer, G. (2003). Political Islam. In: Martin, R.C. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world. (pp. 536–540). Macmillan Reference, New York.

Langer, L. (2014). Religious Offence and Human Rights. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139600460

Lewis, B. (1988). The Political Language of Islam. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Matthes, J., Kaskeleviciute, R., Schmuck, D., von Sikorski, C., Klobasa, C., Knupfer, H. & Saumer, M. (2020). Who Differentiates between Muslims and Islamist Terrorists in Terrorism News Coverage? An Actor-based Approach. Journalism Studies 21(15), 2135–2153. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1812422

McAuliffe, J. (2020). What does the Quran say about Blasphemy? The Qur’an: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

O’Donovan, O., Dukelow, F., & Meade, R. (2018). Freedom? Cork University Press, Cork.

O’Keeffe, A. (2011). Media and Discourse Analysis. In: Gee, J., Handford, M. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. (pp. 441–454). Routledge, London.

Olsson, S. (2021). The Radical Need of a Critical Language: On Radical Islam. MDPI AG 12(4), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040225

Perrin, D. (2017). Medialinguistic approaches. Exploring the case of newswriting In: Cotter, C., Perrin, D. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Media. (pp. 9–26). Macmillan Reference, New York.

Pleshakova, A. (2017). Cognitive approaches Media, mind, and culture. In: Cotter, C., Perrin, D. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Media. (pp. 77–92). Macmillan Reference, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315673134

Rosenthal, F. (2015). Man versus society in medieval Islam. BRILL, Leiden. https://org/10.1163/9789004270893_003

Tibi, B. (2012). Islamism and Islam. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Van Dijk, T.A. (2006). Discourse and manipulation. Discourse & Society 17(3), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506060250

Wallace, R.W. (2007). Revolutions and a New Order in Solonian Athens and Archaic Greece. In: Raaflaub, K.A., Ober, J., Wallace, R., Cartledge, P., Farrar, C. (Eds.), Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. (pp. 49–82). University of California Press, Berkeley. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520245624.003.0003

Notes

1 Samuel Paty is a French history teacher who was assassinated by a terrorist on 16 October 2020 after showing in the classroom Charlie Hebdo's cartoons depicting the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

2 Why Won't Obama Say Radical Islam?, Ken Dilanian, nbcnews, June 13, 2016.

3 The brackets indicate the number of the video in the corpus. For French and Arabic, the translation is also provided. Google Translate was used for the translation which was followed by some rectifications.

Pour citer ce document

Ce(tte) uvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.